Melanesian Mythology Of Solomon Islands

A baby that slaughter ogres. A polygamous man with a tail of a snake. A woman who mated with a bird. All these and more when you explore Melanesia myths.

Author:Jane RestureOct 26, 2023477 Shares238.6K Views

Over many thousands of years successive waves of predominantly Oceanic Negroids and later Austronesians (a Caucasoid and Mongoloid mixture who moved out of Southeast Asia into New Guinea and the chain of Melanesian archipelago, which stretches south to New Caledoniaand New Hebrides - renamed Vanuatuin 1980 - and east to Fiji).

Each new group of immigrants either mixed with their predecessors to form hybrid groups or pushed into the less hospitable regions of mountain, swamp, and jungle.

The pattern of settlement was one of independent developers of innumerable small communities in relative isolation - a process that was constantly modified by external pressure, such as:

- minor migration

- warfare

- trade

- intertribal social gatherings

It is these factors that ensured the continuous diffusion of all sorts of cultural elements including myths.

The manner in which certain stock incidents, elements, and themes of myths became linked in a kaleidoscopic variety of combinations tempts speculation about the cultural layers they belong to and draws attention to the complexity of the area’s cultural history.

It is this diffusion that manifests itself in the continuing process that has produced the rich profusion of cultural patterns that characterize Melanesia today.

The ‘Tindalo’

In the Nggela Islands, aka Florida Islands, a group of islands in Solomon Islands, a tindalo, the spirit or ghost of a dead man who in his lifetime possessed great mana or power, was believed to retain this power after death.

Sometimes a rough image was set up on a sacred spot associated with him, such as his burial place - sometimes simply in a garden, the bush, by the sea-shore, or in his village.

The tindalodid not enter the image but it served as a focus for approaches of a propitiatory and supplicatory nature.

Offerings of food and money were made.

On this and neighboring islands, a tindalomight also take up his abode in another living creature, such as a:

- shark

- snake

- crocodile

- frigate bird

Of Men And Creatures

In the Solomon Islands, as throughout Melanesia, beliefs about origins, not only of men but also of animals, plants, and social customs, are frequently linked with certain archetypal themes, one of which is the myth of the ogre-killing child born to an abandoned woman.

Other related themes concern abandoned women who mate with animals or birds or abandoned children who are suckled by animals or birds.

Very often one of two hostile brothers or one of a band of brothers is regarded as a creator.

The Mysterious Marruni

Then there are the myths about a snake relative who is killed and from whose body comes various forms.

Several districts of New Ireland have stories about snakes as food producers and makers of totems and clans.

One of these stories comes from the district of Medina and is about Marruni, who had a human body that ended in a snake’s tail, which he kept hidden from his wives.

One day, they returned from the garden early without giving the warning signal and discovered him sunning himself.

He sent them away and cut his tail into segments. He gave a clan name to some pieces and from each of these came the people of that clan.

From others came birds, snakes, fish, and pigs.

Marruni is said to have come from the tiny offshore island of Tabar, which seemed to have been the home of the germinal culture of the area, and to have brought the malangginor memorial rights for the dead with him from there.

Extraordinary Serpents

Everywhere in San Cristobal, there were stories about serpents known as figonas, who were thought to be creators.

Hatuibwari of the Arosi district was a winged serpent with:

- a human head

- four eyes

- four breasts

He suckled all he created.

The greatest of all the figonaswas Agunua, who was thought to embrace all the others who were merely his representatives or incarnations.

He made all kinds of vegetables and fruits, but his brother burnt some of these in the oven, making them forever inedible.

Agunua created a male child, who was helpless at caring for himself. So, he created a woman to make fire, to cook, and to weed the gardens

The first drinking coconut from the tree was sacred to Agunua.

The Child Who Kills Ogres

The theme of the ogre-killing child is also common in the Solomon Islands.

The monstrous creature who devours people has many different shapes. He may be an ogre or a giant in human or spirit form, or an animal like a crocodile.

Almost always, the over killers are twins, although occasionally the hero himself is a bird like the cockatoo.

The methods used to kill the ogre are various.

In a story from New Ireland, there was a great devouring pig that caused the villagers to flee to Tabar, an offshore island.

A woman named Tsenabonpil was left behind because she had a swollen leg. Her swollen leg was so heavy it would have sunk the canoe.

Eventually, she mated with a bird and gave birth to a set of twin boys, who killed the pig. Afterwards, Tsenabonpil attached the pig’s hair to a coconut leaf and sent it to Tabar as a sign.

The villagers who took refuge in Tabar returned.

Tsenabonpil allocated them to different clans and assigned them their totems so that they would know how to behave towards one another.

She also taught them magic and other skills.

Dual Souls

In some parts of Melanesia, particularly the southern and central Solomon Islands, there is a belief in dual souls.

According to this belief, one of souls goes to an after-world usually situated either on an island or underground while the other takes various forms.

In parts of the Solomon Islands, it passes into:

- sharks

- fish

- birds

- other animals

- men

- stones

- trees

As a person ages, his companions watch for a creature that by its persistent association with him reveals itself as his future incarnation.

Sometimes, the head of a man is placed in a hollow wooden shark and floated in the sea. Then the soul passes into the first sea creature that approaches it.

Carved Images And Ornaments

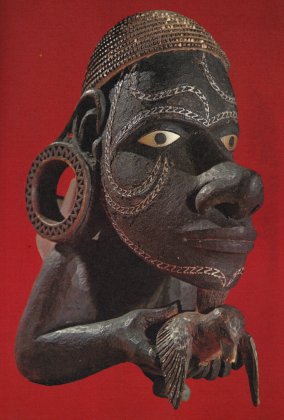

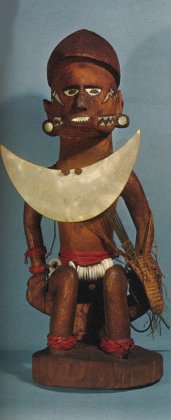

People from the past left behind carvings that represent their belief system. Some of these are now found in museums.

One of them is that of a carved canoe prow ornament made of blackened wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl. It’s taken from Marovo Lagoon - the world’s largest saltwater lagoon - in New Georgia, Solomon Islands.

Attached just above the waterline, it represented the protector spirit of the canoe.

Another one from is a carved and inlaid figure of a shark-headed man. Sharks and other fish play a prominent part in the Melanesian mythology of Solomon Islands.

There’s also a carved wooden image from either Malaita or Ulawa Island in Solomon Islands. The decoration is inlaid mother-of-pearl. The figure probably represents a spirit.

The British Museum stores a sea adaroor spirit, represented in a wood-carving from San Cristobal in Solomon Islands.

Truly, the Melanesia myths of Solomon Islands are filled with interesting creatures.

Jane Resture

Author

Since she embarked on her first world trip in 2002, Jane Resture spent the past decades sharing her personal journey and travel tips with people around the world. She has traveled to over 80 countries and territories, where she experienced other cultures, wildlife she had only read about in books, new foods, new people, and new amazing experiences.

Jane believes that travel is for everyone and it helps us learn about ourselves and the world around us. Her goal is to help more people from more backgrounds experience the joy of exploration because she trusts that travel opens the door to the greatest, most unforgettable experiences life can offer and this builds a kinder, more inclusive, more open-minded world.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles