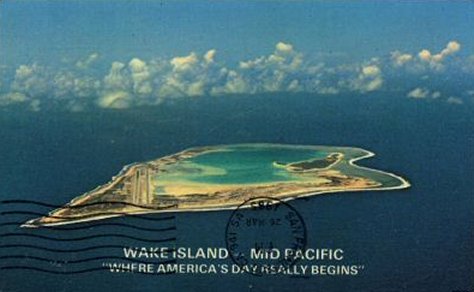

Wake Island - One Of The Most Isolated Islands In The World

Wake is a V-shaped atoll in the northwestern Pacific, north of the Marshall Islands, and lying between Midway and Guam. No two authorities agree on its exact distance from other localities. Since Pan American has flown the distances between Midway, Wake, and Guam many times, we will accept their figures for these stretches and add some of our own for two others.

Author:Jane RestureOct 14, 20222.3K Shares341.8K Views

Wake islandis a V-shaped atoll in the northwestern Pacific, north of the Marshall Islands, and lying between Midwayand Guam. No two authorities agree on its exact distance from other localities. Since Pan American has flown the distances between Midway, Wake, and Guam many times, we will accept their figures for these stretches and add some of our own for two others:

The atoll consists of three islets, Wake islet, the largest, on the southwest, has the shape of a V, the arms of which are about two and three-quarters land miles long. Each arm is continued as a separate islet, there being a narrow channel between it and the end of the arms of the V.

The western ends of the two islets are connected by a sweep of the flat reef, which continues as a narrow border around the three islets. Enclosed is a rectangular lagoon with depths up to fifteen feet. This measures about two and a half miles northwest southeast by one and a third miles wide.

The southeastern portion of the lagoon becomes shallower until it ends in a large expanse of hard white sand which dries at low tide. The entire atoll measures about two and a half by five miles.

Names were given to the two smaller islets by Dr. Alexander Wetmore and other members of the U.S.S. Tanager Expedition, on July 27, 1923. The southwestern islet they called Wilkes, in memory of Lieutenant (later Commodore) Charles Wilkes, leader of the United States Exploring Expedition, visited and fixed the position of the atoll, December 20, 1841. The northwestern islet was named in honor of Titian Peale, artist with the same expedition.

The atoll also has been known as Halcyon or Helsion. According to Dr. William T. Brigham (Index to the Islands of the Pacific) it may have been the same as San Francisco Island, discovered by the Spanish explorer, Mendana, October 4, 1568. The official discovery, however, was made by Captain William Wake in the British schooner Prince William Henry,in 1796.

The island was seen in 1823 by Captain Gardner, in the whale ship Bellona. He described it as being 20 to 25 miles long, with a reef extending two miles from the east end and with detached rocks on the west (probably those on the curving reef). He noted that it appeared well covered with trees. It was also seen by Captain James Hunnewell from the Mentor, December 29, 1824.

Halcyon Island was said by Captain Kotzebue to have been an American discovery, located at about 19 degrees 23' N., 165 degrees 33' E. But after unsuccessful search for it by Captain Sproule of the barque Maria,Captain Brown in the Morning Star,and the U.S. Exploring Expedition, the conclusion was reached that Halcyon was the same as Wake. Captain F.W. Beechey, R.N., in H.B.M. ship Blossom,tried to locate Wake in March 1827, but without success.

Fllowing the careful mapping of the island by Wilkes in 1841, several vessels are recorded as having sighted Wake. These included Captain Sproule, in the barqueMaria,in 1858; and Dr. William T. Brigham "from the masthead of the ship Oraclein 1865."

On March 4, 1866, the Brennen barque Libelle, under command of Captain Tobias, went ashore on the east reef. On board were several prominent passengers and a cargo valued at over $300,000. Among the passengers were Madam Anna Bishop, Miss Phelan, M. Schultz and Charles Lascelles, of an English opera troupe, a Japanese traveller named Kisaboro, and Eugene M. Van Reed, whose account of the experiences appears in The Friend(Honolulu) for September 1866.

Following a hazardous night on the ship, during which waves broke over the vessel, passengers and crew were landed the following day with great difficulty through the breakers. After three weeks on the island, without finding source of food or water, it was decided to try to reach the Marianas Islands in open boats.

On March 27 they set out, passengers in the 22-foot longboat, twenty-two persons, under command of the First Mate, and the captain and remainder of the crew in the gig, with what provisions and water they were able to salvage. After thirteen days of frequent squalls, short rations, and tropical sun, the longboat reached Guam.

The captain with eight persons, in the twenty-foot gig, were not heard of again, although a schooner from Guam went in search. The passengers were strong in their praise of the courtesies received from Francisco Moscoso y Lara, Governor of the Marianas Islands.

Several vessels went to Wake to salvage the cargo, which included several hundred flasks of quicksilver. The sloop Hokulele,with a party headed by T.R. Foster, left Honolulu May 9, 1867, reached Wake on May 31st, left there June 22, and returned to Honolulu July 29, with 247 flasks of quicksilver. A brig from China salvaged another 248 flasks at about the same time.

Thomas Foster, Captain English, and eight Hawaiian divers landed at Wake from the Hawaiian schoonerMoi Wahine in September 1867. Three days after their arrival their schooner, with Captain Zenas Bent in command, mate Wight, and a crew of five, was driven to sea by a gale and not heard again. The salvage party was rescued by the English brig Cleo,Captain Cargell, in March 1868, and returned to Honolulu on April 29, with 240 flasks of quicksilver, some copper, anchor and chain.

In 1883 the German warship Leipzigpassed close to Wake and a careful determination of its position was made.

During the Spanish-American war, several vessels going to and returning from the Philippines stopped and raised the American flag. One of these, perhaps the earliest (according to the World Almanac), was July 4, 1898, by General F.V. Green, commanding the second detachment Philippine expedition from the S.S. China.

Another, also in July 1898, by General Merritt, from the U.S. Army Transport Thomas.This may have been made in the little cove near the eastern end of Wilkes islet, where a section of flagpole had been burned in block letters, "U.S.A.T. Thomas".

The formal annexation of the island by the United States took place on January 17, 1899, according to an account by Commander Edward D. Taussig in the Naval Institute Proceedings for June 1935. He commanded the U.S.S.Bennington which made the voyage from Honolulu to Wake for that purpose.

The landing was made in the cove noted above, and at 3.22 p.m. the American flag was hoisted by Ensign Wetterngell and a salute of 21 guns fired from the Bennington.The position of the flagstaff was determined, from observation on the ship, to be: 19 degrees 17' 50" North and 166 degrees 31' East. The account continues:

"After the salute was fired, the flag was nailed to the masthead with batten, and a brass plate with the following inscription was screwed near the base of the flagstaff:

United States of AmericaWilliam McKinley, President;John D. Long, Secretary of the Navy.Commander Edward D. Taussig, U.S.N.,Commander U.S.S. Bennington,this 17th day of January 1899, tookpossession of the Atoll known as WakeIsland for the United States of America."

During the next decade an occasional American ship stopped, but there is very little recorded history. During this time the island was visited by Japanese poachers, collecting the feathers of sea birds for millinery purposes. Two camps were established: one on the eastern end of Wilkes Islet, where the Tanager Expedition in 1923 found a single wooden shack and a grave; and one across the lagoon near the eastern end of Peale islet, where there was a more extensive camp. This is described in the field notes for July 31, 1923, as follows:

"Back to the Japanese camp for lunch." (It was good field practice to combine lunch eating with careful examination of particular spots, when possible). "The camp consists of the remains of two large frame buildings with galvanized iron roofs, about 18 feet wide, one 20 feet long, one 30 feet long; two smaller buildings; one tank, and one storehouse, raised on posts which are guarded with tin.

Scattered about were a number of barrels, boxes, two large clay water jars, tin cans, and metal kettles. Saw part of a Sydney newspaper, a pile of oakum, bamboo frame with lath trays. There was also a boat, a little larger than a skiff. Made a copy of Japanese inscription inside the bunk house." This later was translated to read something about leaving the island, with the date, November 13, 1908.

In 1912, theU.S.S. Supply stopped at Wake Island. A whaleboat landed some men who planted coconut palms brought there from Guam. No sign was seen of these in 1923.

The Tanager Expedition made an extensive biological survey of Wake from July 27 to August 5, 1923. Their camp was along the ocean beach opposite the landing place at the eastern end of Wilkes Islet. A map of the atoll was made by James B. Mann and Professor Harold S. Palmer, to which were later added determination of latitude and longitude, made from a boulder near the camp.

Meanwhile soundings were made from theU.S.S. Tanager,under command of Lt. Comdr. Samuel Wilder King, laer Hawaii's delegate to Congress. Although the vessel worked as near to the reef as it dared, at only one spot was it possible to reach bottom with 100 fathoms of line; this was about 1500 feet off Heel Point, where a sounding of 85 fathoms was made.

A total of twenty-one species of flowering plants have been found growing naturally on Wake. Much of the surface of all three islets was (in 1923) covered by scrub forest, twelve to twenty feet high. Some of the forest was so dense that one could not walk through it with speed or comfort.

In places, such as the middle portion of the northern arms of Wake and the western ends of Wilkes and Peale, there were areas where trees were lowered and scattered and the undergrowth scrubby, as if here the sea occasionally broke across the rim at time of storms.

The dominant tree on the islands was the Tournefortiaor tree heliotrope, now known to scientists as Messerschmidiaargentea, a species widespread on Pacific Islands. It grows to a height of about 20 feet, with an umbrella-shaped canopy of rosettes of large leaves, covered with silvery hairs. Even large in size but confined to the northwestern end of Wake islet was the "buka" tree (so-called by the Gilbert islanders), Pisonia grandis, with massive trunks of very soft wood and sticky flowers and fruit.

On Wilkes islet, and apparently spreading rapidly along the lagoon beach to the east and north, were tall, wiry bushes of Pemphis acidula.In the interior of Wake were small clumps of kou trees. Cordia subcordata,a hard wood tree, much prized in some regions for woodwork, but here so scrubby as to be worthless.

Growing over trees, rocks and bushes, and forming tangles on the ground, was a kind of morning-glory vine, Ipomoea grandiflora. There also was a small clump of the goat's foot or beach morning-glory, Ipomoea pes-caprae,about the ruins of the Japanese camp on the Peale islet. The rest of the undergrowth consisted of low shrubs, herbs, and grass.

Some species, such a Boerhaavia diffusa,two kinds of purslane (Portulaca lutea and oleracea),Lepidium,and theilima bush (Sida fallax), were of rather general distribution. Other kinds of plants were confined to certain places: pickle weed (Sesuvium portulacastrum)forming meadows at the head of arms of the lagoon, a few small patches of Scaevola, a single patch of a wild cotton (Gossypium hirsutum varietyreligiosa) east of the extreme northeastern bay of the lagoon, and beach heliotrope (Heliotropium anomalum)in places on the ocean beach.

A small patch of tobacco, found near the Japanese camp was doubtless introduced. Two weeds, Amaranthusgraecizans and Phyllanthus Niruri,collected since 1935, probably arrived with Pan American Airways parties, who also introduced several ornamental and garden plants. The three kinds of grass found on Wake are Digitaria Gaudichaudii, found native on Guam; the widespread wiry grass, Lepturus repens; and Bermuda grass, Cynodon dactylon, which follows man to far-away places.

The bird life on Wake consisted of about a dozen species of sea birds, half a dozen or more migratory species, and the flightless rail. The rail, Rallus wakensis, was the only native land bird, and was by far the most interesting species. It stood about 8 or 9 inches high, like a small cockerel or bantum rooster; upper parts dark ashy-brown, underparts similar, barred with white, and chin and upper throat whitish.

It had wings about four inches long, but these were so soft as to have little or no power of flight. It is not at all unlikely that since then this species has become extinct, due to the experiences through which the island has passed. In 1923 the sea birds were of the usual species; petrels, red-tailed tropic bird, boobies, frigate, and terns, already described for islands of the Hawaiian chain and the central Pacific. To the Pacific golden plover, bristle-thighed curlew, wandering tattler, turnstone, sanderling, and sandpiper, doubtless could be added other migratory species of the western Pacific.

Persons who lived on Wake complained of trouble with rats. The species studied in 1923 was a close relative of the Hawaiian rat, another of the Rattus concolor group, widely distributed in the Pacific. The extermination of this rat on Wake was made the subject of much study by the Department of Agriculture experts. Their work was complicated by the presence of the flightless rail, the status of which they did not want to disturb by trapping shooting, or poisoning.

To those who camped on Wake in 1923, as much a pest as the rats were the hermit crabs. One large, red-legged species, Dradanus punctuatus, got into our provisions, ran off with the soap, and combined the activities of pack rats with those of being the garbage department for the island.

In a report on the insects of Wake (Bishop Museum Bul. 31, 1926), 44 species were enumerated. Some were native species, described as new by collaborators in that publication; others were species widespread on Pacific islands. Nearly all, except cockroaches, a sphinx moth, and the Hypolimnusbutterfly, were rather small in size. None was harmful to man, there being no mosquitoes, blood-sucking flies, or venomous species, although a single drywood termite was found in one Japanese shack.

In 1940 additional specimens of insects were collected by Torrey Lyons, garden expert for Pan American Airways. These included such pests of garden crops as tomato loopers, a leaf-cutting bee, and scale insects, some of which followed man to the island.

In 1935 Wake Island was placed under jurisdiction of the U.S. Navy Department by Executive Order, and that same year Pan American Airways established a modern airport, using the south shore of Peale islet, just west of Flipper Point as the site of pier, shops, water tanks, and modern hotel.

By Executive Order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, dated February 14, 1941, Wake was made a national defense area.

Rear Admiral Shigimatsu Sakabara, former commander of the Japanese garrison forces of Wake, signs the surrender document which makes Wake American again. Left to right around the table, on the boat deck of the destroyer escort USS Levy; Japanese Army Colonel Shigeharu Chikamori, Sakaibara, Japanese Paymaster Lieutenant P. Hisao Napasato, Marine Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson, of Santa Barbara, Cal., Commander of the Fourth Marine Air Wing who accepted the surrender in the name of Rear Admiral W. K. Harrill, Army Sergeant Larry Watanabe of Honolulu, official interpreter at the surrender, and Colonel T. J. Walker Jr., Sanderson's Chief of Staff. Standing (center with pipe) is Colonel Walter L. J. Baylor, last man to leave Wake Island.

Jane Resture

Author

Since she embarked on her first world trip in 2002, Jane Resture spent the past decades sharing her personal journey and travel tips with people around the world. She has traveled to over 80 countries and territories, where she experienced other cultures, wildlife she had only read about in books, new foods, new people, and new amazing experiences.

Jane believes that travel is for everyone and it helps us learn about ourselves and the world around us. Her goal is to help more people from more backgrounds experience the joy of exploration because she trusts that travel opens the door to the greatest, most unforgettable experiences life can offer and this builds a kinder, more inclusive, more open-minded world.

Latest Articles

Popular Articles